Artifacts in sunset photography

Sunsets are difficult to photograph, and green flashes are even more

difficult to capture. The brightnesses of the Sun, the sky, and the

foreground usually differ by many orders of magnitude, and differ by

additional large factors from one sunset to another. Even within a few

minutes, the brightness can change drastically. At moderate latitudes,

the correct exposure changes by about a factor of 2 (one full stop) every

minute.

In addition to the difficulty of getting the exposure right, there are

several deceptive effects that can lead an unwary observer to suppose that

a green flash has been captured, when in fact all the picture shows is

some quirk of the imaging method used. These misleading appearances in

pictures are generally called artifacts .

Optical artifacts

Regardless of the technology used to capture the image, there are inherent

imperfections in the optical image itself that occasionally are visible.

For example, Gunta Norman has a

photograph

on the Web that shows a green patch on the horizon, just left of center.

It isn't a

green ray,

but what optical workers call a “ghost” — an

internal reflection in the lens itself. In this case, the broadband

anti-reflection coatings used on the Canon lens were designed to minimize

reflections across the spectrum by reducing them to the lowest possible

value in the red and blue; but this leaves a little reflection in the

middle of the spectrum (i.e., in the green). The residual reflection

is very weak, but it's visible in this picture because the Sun is so

overexposed. (Notice that the green reflection has disappeared in the

next frame, taken 18 seconds later, after the Sun had set behind a rock.)

Ghosts like this are typically seen in the image at a position

diametrically opposite to the overexposed Sun. In the picture mentioned

above, the Sun is to the upper right of center, and the ghost to the lower

left. This reflection about the center of the image is a dead giveaway

that the spurious image is a ghost.

Such internal reflections are more common in zoom lenses, because their

large number of elements (and surfaces) provide more opportunities for

reflections to occur. Here's another example, taken with the 6× zoom

lens of a Canon G9 by Mike Maffett, M.D., in May of 2009. (The ghost is

the green blob a little below the center, superimposed on the dark ridge

in the middle distance.) He has another such image,

taken about 3 minutes earlier, with the Sun in the upper right and the

ghost symmetrically placed in the lower left. The green reflection inside

the G9's zoom lens is dimly visible in photos of the camera on the Web

(e.g.,

here).

Such internal reflections are more common in zoom lenses, because their

large number of elements (and surfaces) provide more opportunities for

reflections to occur. Here's another example, taken with the 6× zoom

lens of a Canon G9 by Mike Maffett, M.D., in May of 2009. (The ghost is

the green blob a little below the center, superimposed on the dark ridge

in the middle distance.) He has another such image,

taken about 3 minutes earlier, with the Sun in the upper right and the

ghost symmetrically placed in the lower left. The green reflection inside

the G9's zoom lens is dimly visible in photos of the camera on the Web

(e.g.,

here).

Such ghosts tend to be more prominent with digital cameras than with film,

apparently because the focal-plane sensor in digital cameras is a specular

reflector, while film is a more diffuse reflector. (Digital cameras

produce other artifacts as well; see

below).

Sometimes the ghost is prominent only at one end of the zoom range; the

spacings of the lens elements change with the zoom setting.

Mila Zinkova has a really splendid example of ghosts, in her picture of

crepuscular rays

at

this

web page.

Photographic artifacts

Silver-halide photography has been around for all of our lives, so we're

accustomed to its quirks. Experienced photographers are aware that an

overexposed image of the low Sun will turn out yellow, or even white, on

color film, even though its nominal color is reddish orange or red.

This effect of overexposure is due to saturation of the film; because the

low Sun is reddish, the red-sensitive layer saturates first.

This same problem occurs with digital cameras.

Another artifact of overexposure in color photography is that an

overexposed green flash shows very washed-out, pale colors on reversal

films like Kodachrome and Ektachrome. Underexposure is preferable, if you

want to capture the highly saturated colors typical of green flashes.

But even at best, the colors that can be reproduced on film are much less

saturated than the colors of real green flashes.

Other photographic artifacts that might show up are halation and

solarization, though the latter requires very extreme overexposure.

The point is, the photographic process has been around long enough that its

vices are well known, and experienced photographers will be aware of them.

If you know what can go wrong, and keep an eye out for it, you aren't

likely to be fooled.

Digital photography

These days, digital cameras are almost as common as digital watches, the

fad of a generation ago. But digital cameras are new; we're not used to

their quirks. So it's easy to be deceived when the camera does something

it was designed to do, but isn't want you want it to do.

A common example is automatic adjustment of color balance. Most digital

cameras look at the relative amounts of the primary colors in the scene,

and then try to adjust the color to make things look “right”.

If you take a picture in open shade, where the illumination comes from

the blue sky, the camera reduces the brightness of the blue sub-image

and increases the gain for the red, so that objects in the picture come

out with approximately their “correct” colors.

If you take a picture indoors by incandescent light, the camera

compensates for the reddish illumination by boosting the blue and reducing

the red content of the picture.

Of course, the eye does all this

compensation automatically; it's not so easy for the camera.

That's why we had “daylight” and “tungsten”

films in silver-halide

photography, and professional photographers carried around a set of

color-compensating filters to handle the variations in lighting.

The fact that electronic cameras can compensate for the lighting

automatically is often regarded as one of their big advantages.

However, when you try to photograph a sunset, the Sun is very red, as are

any clouds low on the horizon. Often, a digital camera will look at all

this red stuff in the picture and decide to shift colors in the opposite

direction. Sometimes the effect of that is to produce a picture with a

pronounced greenish cast.

Sometimes people unfamiliar with this quirk will discover a greenish

picture in a series of images they've taken of a sunset, and jump to the

conclusion that they've photographed a green flash — or, better

yet, one of those rare

“green ray”

displays.

Sometimes they send them to me and ask if this is really so, and I have to

explain that, no, that's just the way the camera works. It can shift the

balance from one picture to the next, and back again, depending on just

how much of the red cloud is included, or where it is in the frame.

The camera maker would insist that this isn't a bug, it's a feature.

Well, 99% of the time, for most people, it is a feature.

But for those of us looking for green flashes, it's a bug.

A related problem is automatic exposure adjustment. Many digital cameras

don't really adjust the exposure at all; they just adjust the gain of the

image so that a tiny fraction of the pixels are saturated. Those

saturated pixels might be on the Sun itself, or a cloud near it.

Once again, the result is a funny-looking picture.

There are some good examples at

Crazy Joe's Surflounge,

where the red aureole of the low Sun has saturated the red pixels

near the Sun, and turned down their gain, leaving a zone of

nearly-saturated green ones a little farther out. This produced a

greenish ring around the overexposed image of the Sun — an artifact,

not a green flash.

Often a big giveaway that something isn't really in the sunset sky is the

fact that the photographer (and other people nearby) didn't see anything

unusual at the time the picture was taken. Now, real

green flashes are pretty spectacular: people notice them. It's hard

enough to capture the ones you actually see. If you didn't see a flash,

that's usually because there wasn't one. The camera is very unlikely

to catch a flash missed by everyone watching the sunset (unless a very

long telephoto lens was used).

Sometimes it's possible to re-adjust the color balance of a

greenish picture in such a sequence to establish that the color is

just an artifact of the color balance. But this is tricky

to do, because digital images are usually stored in a way that displays

correctly on a computer or TV monitor. But these monitors usually produce

brightnesses that are roughly proportional to the square

of the signal fed to them. So a compensating nonlinearity is built into

the digitized image.

That means that we have to undo this nonlinearity to get back to numbers

that are proportional to brightnesses, before we can play games with color

balance by adjusting the gain of the R, G, or B channel. And then, you

find that the overexposed red channel had its data truncated at 255, so

you can't make a realistic adjustment of the truncated values. So it

often isn't easy to process the image to show how the phony green color

was produced.

Finally, many digital cameras these days — especially the ones in

"smart" cellphones — have image-processing software that tries to

"enhance" pictures in various ways. For example, most people's pictures

contain images of their friends' faces; so the software tries to find

things that look like faces, and selectively adjust the contrast and

resolution of just those parts of each picture. This

mangles sunset images in ways that cannot be undone. The only way to

avoid such defects is to set the camera to record images in RAW mode.

Cellphone pictures of sunsets taken in the ordinary default mode are

useless. If you want to send me a sunset picture, make sure you save the

image in RAW mode, or I won't be able to tell you anything useful.

Another artifact of digital cameras is due to charge spill in CCD

detectors. Bob Collin, of Beaverton, Oregon, sent me this fine example:

What you see here is leakage along the columns of the CCD, caused by the

overexposed solar image. I'd have expected this streak to appear red, but

maybe the green hue is due to a color-balance shift of the kind discussed

above: notice that the clouds around the Sun appear yellow, rather than

the reddish orange you'd expect.

In any case, this is a camera artifact, not an atmospheric phenomenon.

What you see here is leakage along the columns of the CCD, caused by the

overexposed solar image. I'd have expected this streak to appear red, but

maybe the green hue is due to a color-balance shift of the kind discussed

above: notice that the clouds around the Sun appear yellow, rather than

the reddish orange you'd expect.

In any case, this is a camera artifact, not an atmospheric phenomenon.

What's happening here is that the Sun's bright image produces vastly more

photoelectrons than the maximum capacity of the little

“electron wells” in the chip that

hold and transport the charges forming the image. It's sort of

like those plastic ice-cube trays that have little grooves between the

compartments, so that you can run water into one, and it will

progressively flood the others. Here, it's electrons instead of water,

but the overflowing process is analogous: excess charges flood the column,

producing a bright artifact in the image, as if it had been exposed to a

vertical strip of light in the image plane.

Just to show that this isn't an uncommon problem, here's another image

with a green charge-spill artifact, provided by Lou Adzima here in San

Diego County. This image was “taken 8/30/06 with a D70 Nikon camera

with a 18-200MM lens with a normal UV filter”; a frame taken 4

seconds later, but with the Sun out of the frame, shows no such green

stripe.

Just to show that this isn't an uncommon problem, here's another image

with a green charge-spill artifact, provided by Lou Adzima here in San

Diego County. This image was “taken 8/30/06 with a D70 Nikon camera

with a 18-200MM lens with a normal UV filter”; a frame taken 4

seconds later, but with the Sun out of the frame, shows no such green

stripe.

[The black stripe at the bottom is a different side-effect of extreme

overexposure. Apparently the intense illumination at the solar image has

made the column “leaky”, so that it failed to shift out all

the image charge from the more distant rows, which have to be passed along

the electronic “bucket brigade” more times than those at the

top. So electrons that should have contributed to the brightness at the

bottom of the affected columns failed to appear in the readout, and this

area came out black!]

Yet another kind of digital-camera artifact is due to excess infrared response.

Les Cowley shows a nice example on

this page:

a camera has produced an infrared image of the low Sun when the extinction

was so great that it was invisible to the eye. Of course, the purple

color is entirely artificial.

So common are the artifacts of digital photographs that

one Web

page lists dozens of pieces of software that are available to

“correct” the commoner ones. A quick search with Google

turned up additional pages that discuss these problems; most

are devoted to the rather obvious aliasing and

compression artifacts, but others are mentioned. There's also a comparison of

digital and film photography.

Video

Things are even trickier with videos, because video images go through much

more complicated processing. Some of this involves lossy data

compression, which throws away some of the details of the actual scene.

But in addition to that, the data are separated into brightness and color

(for reasons historically connected with making color TV compatible with

the black-and-white system that preceded it); and the color information

(called “chroma” in the video world) is separated into two opponent

channels, red-green and blue-yellow, even though the image capture is

usually done in terms of RGB.

This opens up further possibilities for mischief, if anything goes wrong

in the electronics or the recording apparatus. And of course most video

cameras also have the automatic color adjustment (known as

“white balance” to the video people) that digital cameras

have. So there are more ways for things to go wrong.

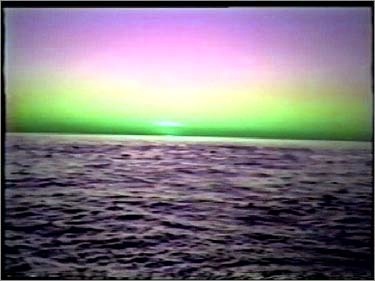

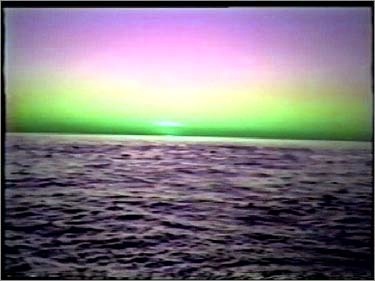

A nice example of this was sent to me by Alan Dean Foster, who took a

sunset video in Australia. His sunset sequence shows occasional frames in

which the red sky at the horizon turns bright green. At first glance,

this looks like a real phenomenon, because the sky and sea are still

nearly the same color in the green-horizon image as in adjacent

red-horizon ones. Here are his examples:

and

and

I tried adjusting the color balance, and quickly found that no possible

shift in color balance could turn one frame into anything like the other.

So the green image is clearly not due to a color-balance

artifact.

However, inspection of the video frame by frame shows that the green

frames appear suddenly and very briefly, with no smooth transition

between red and green frames. Even the briefest green flash lasts several

tenths of a second; but these green frames appear from nowhere and

disappear just as abruptly; some are just single frames sandwiched between

normal red ones, and the longest green sequence lasts only a tenth of a second.

This certainly isn't anything related to green flashes.

Furthermore, each green frame has some

garbage at the bottom edge, indicating some synchronization problem

in the video system.

(You can see this at the bottom edge of the green frame above.)

And it's preceded by red frames with the same

problem. This strongly suggests a video artifact of some kind.

It occurred to me that maybe the sense of the red-green chroma signal was

getting reversed, so that what should have been red was displayed as green

and vice versa.

If that were the case, I should be able to re-create the green frame, or

something like it, simply by disassembling the red frame into its red,

green and blue components, swapping the red and green, and then

re-combining them into a color image. (On Linux, it's easy to do this

with the ppmtorgb3 and rgb3toppm commands.) I did this;

here's the result:

and

and

On the left, you have the red frame with the red and green swapped; on

the right, the original green frame from the video.

I think the similarity is close

enough to establish this as the correct explanation.

The reason the sky (and sea) looked nearly the same in both red and

green frames is that the sky is mostly blue, with very little red

or green content. So swapping red and green hardly changes

the sky at all.

Cellphone cameras

A particularly deceptive device to use in sunset photography is

the cellphone camera, because modern ones do a lot of image

processing before saving the image. The worst feature of these

cameras is to segment the image into what some programmer thought

would be interesting features (like faces, for example), and then to apply

local processing (like sharpening, and exposure adjustment)

to those areas, rather than to the whole image. On top of this, the

artifacts are further disguised by saving the image in compressed form,

usually JPEG. In particular, video is almost always saved in compressed

form, because of limited storage space.

One of the tricks used in these cameras is to manipulate the exposure

levels in different areas of the image. And this trick invariably is

used in sunset pictures, because the dynamic range of the scene far

exceeds the 8-bit capacity of common image-storage formats.

Unless the original image data are saved in RAW format, these images

and videos are hopelessly distorted, and cannot safely be interpreted.

Please don't send me cellphone images or videos that were not saved as RAW

images; it's impossible to make sense of them. A good rule of thumb is

that the more modern and expensive phones produce more garbled pictures.

The Moral

The lesson to be learned is: don't trust digital or video images, unless

you know all the ways they can go wrong.

Copyright © 2004 – 2009, 2012, 2021, 2024 Andrew T. Young

Back to the ...

photographic advice page

GF pictures page

GF home page

Such internal reflections are more common in zoom lenses, because their

large number of elements (and surfaces) provide more opportunities for

reflections to occur. Here's another example, taken with the 6× zoom

lens of a Canon G9 by Mike Maffett, M.D., in May of 2009. (The ghost is

the green blob a little below the center, superimposed on the dark ridge

in the middle distance.) He has another such image,

taken about 3 minutes earlier, with the Sun in the upper right and the

ghost symmetrically placed in the lower left. The green reflection inside

the G9's zoom lens is dimly visible in photos of the camera on the Web

(e.g.,

here).

Such internal reflections are more common in zoom lenses, because their

large number of elements (and surfaces) provide more opportunities for

reflections to occur. Here's another example, taken with the 6× zoom

lens of a Canon G9 by Mike Maffett, M.D., in May of 2009. (The ghost is

the green blob a little below the center, superimposed on the dark ridge

in the middle distance.) He has another such image,

taken about 3 minutes earlier, with the Sun in the upper right and the

ghost symmetrically placed in the lower left. The green reflection inside

the G9's zoom lens is dimly visible in photos of the camera on the Web

(e.g.,

here).

What you see here is leakage along the columns of the CCD, caused by the

overexposed solar image. I'd have expected this streak to appear red, but

maybe the green hue is due to a color-balance shift of the kind discussed

above: notice that the clouds around the Sun appear yellow, rather than

the reddish orange you'd expect.

In any case, this is a camera artifact, not an atmospheric phenomenon.

What you see here is leakage along the columns of the CCD, caused by the

overexposed solar image. I'd have expected this streak to appear red, but

maybe the green hue is due to a color-balance shift of the kind discussed

above: notice that the clouds around the Sun appear yellow, rather than

the reddish orange you'd expect.

In any case, this is a camera artifact, not an atmospheric phenomenon.

Just to show that this isn't an uncommon problem, here's another image

with a green charge-spill artifact, provided by Lou Adzima here in San

Diego County. This image was “taken 8/30/06 with a D70 Nikon camera

with a 18-200MM lens with a normal UV filter”; a frame taken 4

seconds later, but with the Sun out of the frame, shows no such green

stripe.

Just to show that this isn't an uncommon problem, here's another image

with a green charge-spill artifact, provided by Lou Adzima here in San

Diego County. This image was “taken 8/30/06 with a D70 Nikon camera

with a 18-200MM lens with a normal UV filter”; a frame taken 4

seconds later, but with the Sun out of the frame, shows no such green

stripe.

and

and

and

and