Having finally learned a little about how to avoid some LaTeX problems, I thought I'd record some painful lessons here, in hopes of saving other writers some of the agony I went through. This page deals with the interface between LaTeX and the rest of the formatting system.

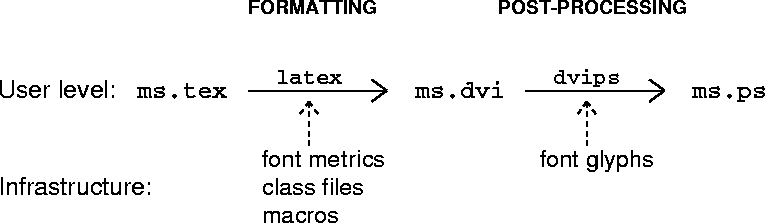

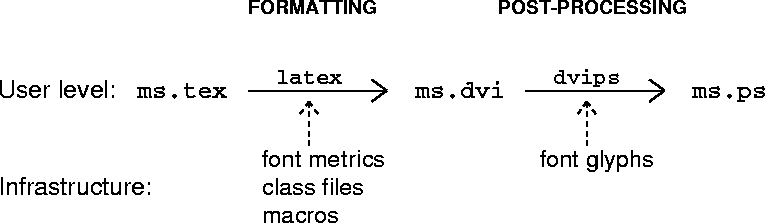

Let's first distinguish between the commands used by a writer, and the infrastructure that allows documents to be previewed on-screen and printed on paper. Here's a crude diagram of how it works:

If your input file is called ms.tex, the formatted output of the latex command is a file ms.dvi, which can be turned into a printable PostScript file ms.ps by the dvips command.

If you have a printer, or a print spooler, that can handle PDF files directly, you may not need the ms.dvi file; then you can use the program pdflatex to produce a PDF version in one step. (However, there are complications: pdflatex can only absorb figures that have been converted to PDFs, but plain latex can embed EPS figures in its output.)

This is the surface the user sees, but a lot more is involved beneath it. Let's look first at the user commands, and then at the infrastructure.

The commands used vary from system to system. The general procedure, of course, is similar everywhere; but the particular commands and filenames I'll mention refer to Debian Linux only. (Even other flavors of Linux sometimes do things differently — as I discovered to my grief.)

You start with a text editor (usually vi or emacs), and edit a file of input for LaTeX. Run the latex command on it, and (if you are lucky) you get a *.dvi file out. But that DVI file is useless without fonts and a way to display the formatted document.

That's because TeX and LaTeX don't know anything about the characters (known as glyphs in this business) that a human being can read. Formatters only know how much space the glyphs take up on the page. All the formatter does is reserve space for things; the DVI file only tells where every character goes on the page, not what it looks like. (See the fonts page for more information about fonts.)

To display the formatted text in readable form, you need a post-processor (like xdvi or dvips), which puts the glyphs from a font (and the images from graphics files) where the *.dvi file says they should go on the page.

But glyphs are represented in different ways, depending on the output medium. On screen, they're rows of little dots; a computer screen is a dot-matrix printer. So you need a map of where the dots go: a bitmapped font. Screen fonts are always bitmapped.

But the standard (especially in technical publishing) for printing on paper is PostScript (PS, for short). And PostScript fonts are (usually) outline fonts ; the “rasterization” of the glyphs occurs in the PS interpreter, long after the *.ps file is written.

Unfortunately, these post-processors are usually called “printer drivers” by the TeX people — a usage that conflicts with standard UNIX/Linux terminology.

Fonts involve another layer of complexity. There are thousands of font files in even a “vanilla” installation of TeX. Most of them are in the format used by some digital font foundry, like Adobe — not the formats needed by TeX for font metrics, or by dvips for output.

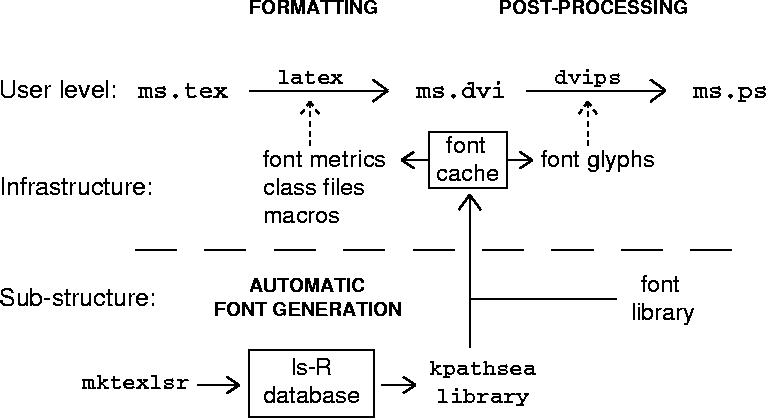

When one of these programs needs font information, it turns to a font cache stored under /usr/share/texmf/fonts/. The tfm subdirectory holds font metrics for TeX; tfm means TeX Font Metrics.

But there are so many font files available that it's impractical to have them all pre-converted to the required formats. Instead, latex, dvips and other programs look to see whether a font is in the cache when it's needed. If it isn't, they use routines from a path-searching library called kpathsea to look for the font information in some other form. If the font is found, appropriate format-conversion programs and scripts are invoked to create the font on demand, and add the result to the cache.

Information on how the font system is organized is available in the file /usr/share/doc/texlive-doc/fonts/fontname/index.html .

Here's a diagram indicating roughly how this works:

Because these programs have thousands of files available, it's inefficient to search the whole /usr/share/texmf directory tree every time something is needed. Instead, the tree is indexed, and the index is stored in the /usr/share/texmf/ls-R database. This file, created by a program named mktexlsr, is automatically updated when a new font is added to the cache.

Or at least it should be. Often, you find that the database file isn't writable by ordinary users. Or one of the font-cache directories isn't writable when you format a file that needs a new font. Then there are problems.

The kpathsea library is also used to locate macro packages, and other files needed in formatting text. Even TeX input files like testpage.tex can be found this way. [The diagram really should have dotted lines all over the place to show the interactions, but I've left them out to keep it (relatively) simple.]

So kpathsea provides a sort of sub-infrastructure for the whole TeX formatting system. Unfortunately, it's well concealed from the user. Your only command-line access to it is the kpsewhich command, which has rather obscure documentation; see info kpsewhich.

Documentation for the kpathsea library is available at both the kpathsea Web page, and the /usr/share/doc/texlive-doc/kpathsea/kpathsea.pdf file, which can be displayed directly with the texdoc kpathsea command. Section 6.3 of that document tells how TeX finds the glyphs of a given font.

And how does the texdoc script find that documentation file? Why, it uses kpsewhich, of course.

Actually, it's better to convert directly to PDF by using pdflatex instead of regular latex, because there are fewer transformations to go through. (See the LaTeX to PDF page for details.)

It's best to include the actual fonts in the PDF document, so people reading it won't see missing or incorrect glyphs. Use the pdffonts program (from the poppler-utils Debian package) to see which fonts are actually in a PDF file.

But Ghostscript has its own way of accessing fonts; see https://www.ghostscript.com/ for details.

Furthermore, gs usually introduces dithering artifacts in PostScript images. So you must be careful in using gs either directly or indirectly.

This brings us to the problem of including figures in documents.

Figures are like font glyphs: TeX decides where they should go, but the actual image data are separate from the *.dvi file. Only when a PostScript or PDF version of the document is made will the actual images be incorporated into the output file. Preparation of figures for inclusion in LaTeX documents is so complicated that I have a separate page devoted to this problem.

Briefly, there are two different ways to go: either convert all the figures to PostScript (actually, Encapsulated PS, or EPS), or convert them all to JPEG, PDF, and PNG. If you merely want to print the document on a PostScript printer, it's simplest to convert everything to PostScript. If you need to make a PDF file, the second way (JPEG, PDF, and PNG) will produce slightly smaller files and (usually) better image quality.

Behind the scenes, there are many other programs that get called, directly or indirectly, by the ones you use at the command line. They fall into two main groups: things used by TeX, or whose products are used by TeX; and those used by the PostScript post-processors (mainly, gs).

Fonts are complicated, but there are good explanations in the Font HOWTO and Alan Hoenig's book TeX Unbound.

So the font glyphs must be available to post-processors like dvips and dvipdfm. As the dvi file already tells where they go on the page, the font metrics are not needed here. So glyphs and metrics are stored separately.

Note that you must have the resolution of your printer(s) available to the post-processors, if they are to produce printable files from bitmapped fonts. That means you must run tlmgr and set up support for each and every printer on which you want to print formatted documents.

If you need to include PS graphic images in figures, use the graphics macro package (or, preferably, its more capable cousin, graphicx). Use texdoc graphics to read the local Catalogue, or texdoc -l graphics to find the documentation on your system.

I have pages on converting PS to EPS, on conversions between PS and raster graphics formats (such as PNM), and on converting PS to PNG.

Copyright © 2005, 2006, 2010, 2021 Andrew T. Young

or the

alphabetic index

or my website overview page