It's often said that the flat-Earth (or, to be more pedantic, the plane-parallel) model of the atmosphere is satisfactory near the zenith. To show just how nearly flat the Earth is, compared with the depth of the atmosphere, here's a picture, drawn to scale:

The heavy line at the bottom represents the surface of the Earth. The light lines are the levels at which the pressure is (from the top down) 10%, 20%, … , 90% of the pressure at the surface. All these lines are arcs of circles, concentric with the Earth's center (which is far below the bottom of your screen). The top (10% pressure) level is about 16 km above the surface.

Looks pretty flat, doesn't it?

The picture should convince you that the flat-Earth approximation is good enough to deserve a closer look.

Now let's consider refraction in strictly plane-parallel geometry.

Initially, we assume a single homogeneous layer of refractive index n. The observer is at O; the observed zenith distance of an object is z0 . Applying the sine law of refraction at the refracting upper surface gives

But because all the verticals are parallel in this model, the angles z0 and z1 are equal; so

As Newton showed in his famous “Opticks”, this can be extended to a second layer above the first, and then to a third. The product (ni sin zi) at every horizontal interface remains equal to the sine of the zenith distance at the top of the whole stack, where n = 1 exactly; in particular, n sin z0 at the bottom remains equal to sin z at the top of the stack. It is as though there were only the bottom layer, of index n.

The refraction, r, is the difference of the angles z0 and z2 in the diagram above. That is,

But the previous equation gave us sin z2 as a function of z0 ; taking its arcsine gives

Consequently, the exact expression for the refraction r in the plane-parallel model is

However, this exact result isn't very informative. More insight into the behavior of the refraction can be obtained from a useful approximation.

Now we can use the trigonometric identity for the sine of a sum of angles to write

But we know from observation that r is generally less than about half a degree, or 0.01 radian. So, to better than a part in ten thousand, we can set sin r ≈ r, and cos r ≈ 1, making

Plugging this expression for sin z2 back into the refraction-law result above, we get

solving for r gives

or

This is the flat-Earth approximation for the refraction. It's just proportional to the refractivity at the observer, and the tangent of the apparent (refracted) zenith distance.

The exact formula for refraction on a flat Earth

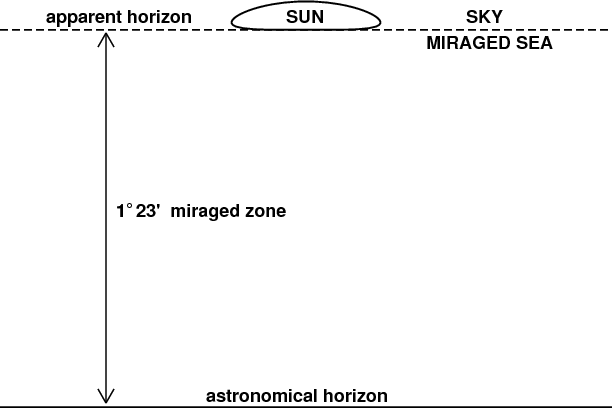

allows one to draw the shape of the setting Sun that would be observed in

this situation. Here it is, at the right:

The exact formula for refraction on a flat Earth

allows one to draw the shape of the setting Sun that would be observed in

this situation. Here it is, at the right:

The Sun would appear to set on a surface about 1.4° above the astronomical horizon. The drawing shows the Sun's exact shape at the moment when its lower limb touches this false apparent horizon; the whole disk of the Sun is shown. Everything between the false horizon and the astronomical horizon would be filled with a gigantic refracted image of the (flat) Earth's surface, which would appear concave.

Qualitatively, this highly flattened sunset image resembles what's seen by an observer inside a duct; see the second image in the simulation showing a wide blank strip. But quantitatively, the negative dip here is an order of magnitude larger than in that case, which is already very unusual.

Although the details of the mirage — or, more likely, looming — in this huge blank strip would depend on the density structure of the flat atmosphere, Newton's proof mentioned above guarantees that all sunsets in the flat-Earth model must have exactly this bizarre appearance. In particular, the enormous elevation of the false horizon depends only on the refractive index of air at the observer — a quantity known to many decimal places from laboratory measurements.

The fact that no real sunset on Earth ever has these characteristics can be taken as observational evidence that the Earth is round, not flat.

Copyright © 2003 – 2008, 2018, 2020, 2021, 2025 Andrew T. Young

or the GF home page

or the

overview page